Planned Giving For Everyone

December 29, 2018

Many consider planned giving a luxury reserved for a rich few. They’re wrong.

Get that out of your head right now.

Planned giving is something any of us can do. And those stories about a social worker or janitor leaving over $100K or over a million dollars to charity. Those are real. It’s obviously important that wealthy individuals set up planned giving, but it’s also important for those who are in lower and middle economic classes to set up planned giving, too. For instance, in The Givers, author David Callahan makes the case that concentrated donations from a select few could misprioritize the cause areas that benefit the rest of us.

The impact of planned giving is enormous. It lets a merely rich person give a gift that only the super rich could afford. A middle-class person can give an upper-class gift. And a person with little could give a gift a middle-class person would typically give. Planned giving takes your giving up a notch.

As a non-millionaire in my 30’s, I can speak to this fact personally. I’ll be giving much more through planned giving than I could ever give traditionally. My age doesn’t stop me from starting now either.

There’s also the notion that planned giving is just too complicated. While that can be the case for some aspects of planned giving, planned giving is often quite easy. My gift to you is showing you the easy and navigating you through the initial parts of the more complicated.

No, you can’t take all those things with you

You should definitely give what you can now.

There are several reasons for giving now. One is that giving now is cheaper than giving later in terms of the good you can buy, and not giving now can make things worse for the world. Doing good itself can even earn a sort of compounded interest over time, and you can’t talk yourself out of giving if you’ve already done it. Another big reason is that if giving now means helping more future people who don’t yet exist, then your gift in the present has much more impact.

In a previous post I recommended giving at least 1% to charity until you have enough for retirement and then to give at least 10%. And if you reach the age where you have your remainder years, debts, and other expenses covered, then you can simply donate whatever you make (earn to give). I follow this myself. My annual average for giving is solidly over 1% since I still have to work on retirement savings.

But even if you follow this giving now approach, there are still those assets that you won’t be able to give until your death.

Here are some of those assets (not all may apply to you):

What’s in your savings, checking, and brokerage accounts for regular living expenses and emergency funds

What’s in your retirement accounts

Your Health Savings Account balance

Home or other land (possibly income earning)

Complicated assets like intellectual property and closely held stocks

Personal tangible property (paintings, collectibles, et cetera)

North of 90% of people don’t include a charitable beneficiary or do any planned giving. That’s terrible because your planned giving gift (those items mentioned above) will often be more than any gift you could have ever given otherwise.

You’re never too young to learn (and do) planned giving

Before I turn off the more youthful among you, let me remind you: you die, too, and you don’t know when. While it’s likely later than sooner for you youngsters, that’s not always the case. Car crashes really do kill people, and they’re not health dependent.

Oh yeah. We’re going to be talking about your mortality.

Here’s a wonderful life expectancy simulation tool using data from the Centers for Disease Control. You can put your own details in there, but I’ll use mine as an example and walk you through it.

I’m not quite up in years yet, but no one mistakes me for a 25-year-old. I’ll turn 37 soon. Using this simulation tool, there’s an 82% chance I’ll live over 30 more years. Pretty sweet odds on me living awhile, which I’m a big fan of.

But there’s also a one in 50 chance I’ll die within the next ten years. That’s nontrivial. For round numbers, let’s say within that 10 years I’m able to raise my assets to $100K (retirement, emergency funds, checking, et cetera). That means that having planned giving in place has an expected value of $2,000 ($100K x 2%) in those ten years.

And that expected value gets larger as you get older and have more wealth (and fewer years of life remaining). Now let’s say I have $500K in assets and I’m twenty years older at 57. Now my risk of death over the next ten years is 15%. That means that having planned giving in place has an expected value of $75,000 ($500K x 15%) in those ten years.

Move my age dial another ten years to 67 and give me $1M in assets. Now my planned giving has a ten-year expected value of $230K ($1M x 23%). Of course, minus a breakthrough from the SENS Research Foundation, all those remaining assets will go to charity eventually. But only if planned giving is set up.

Identifying your financial responsibilities

I’m not a big fan of passing on unneeded wealth to remaining family. Of course, some of us have dependents who rely on us for our income. But there’s a solution for that outside of inheritance.

It’s called life insurance. Research and get life insurance.

In many cases, life insurance does its job at taking care of dependents better than inheritance. It also simplifies your planned giving. Buy life insurance and those other folks who rely on you are taken care of.

(Technical note: If you don’t want a person getting all the life insurance money in a bundle, you can set a trust as a beneficiary and have the trust give a longer payout rate. Consider a KISS trust, discussed later.)

You may also find that you no longer need an existing life insurance policy. Perhaps your dependent is now financially independent. No sweat. Make a charity or donor-advised fund the beneficiary. If your policy is paid up and you make the beneficiary irrevocable, you can likely even take a tax deduction. We’re keeping things as easy as possible for everyone, so we won’t go into setups where the charity pays the insurance.

If you’re not insurable due to your age or other factor, there are still some ways to take care of those who will rely on your income. You can always name individual beneficiaries in the approaches we’ll get into later.

When considering the needs of a dependant, I’d encourage you to plan for leaving a set amount rather than a remainder. This has you focus on actual needs, simplifies your planning, and maximizes your charitable gift.

Setting account beneficiaries—planned giving’s easy button

What do you think of when you think of planned giving? Maybe some attorney drawing up a will or a trust comes to mind? That’s certainly not the easiest way to do it, nor is that the way that applies to most people.

Most bank accounts (including retirement accounts, health savings accounts, and certificates of deposit) have options to transfer assets to another entity upon your death. These are called transferrable or payable upon death accounts. The particular name depends on whether it’s an investment or savings account, but the purpose and setup is the same.

Setting a charitable beneficiary for these accounts is really easy. Most banks make this so easy that you can do it online. Fidelity bank even annoyingly prompts you to set it up until you fill it out (as they should).

If for some reason a bank doesn’t let you set up a charity as a beneficiary, that’s inexcusable. This is not an issue for most major banks, but if a bank doesn’t have this ability, it’s worth considering changing banks and letting them know why. Shame on them.

Why is setting a beneficiary within an account often better than a will? For one, an account beneficiary is super easy to set up and doesn’t cost anything. Secondly, it’s faster. The account funds normally pay to the charity within a few months from notification of death.

For comparison, even if you complete a valid will that isn’t contested, it can still be up to a year or more in probate court from the date of death until the charity sees the money. That’s a long and needless delay. Using a will can also open up those assets to avoidable taxes and creditors. Plus, a will can be challenged more easily than a payable on death account.

As a caveat, you don’t get any immediate tax write-offs by setting a charitable beneficiary for an account. The concept behind why is that the beneficiary here is revocable. Gifts need to be irrevocable for tax deductions to be considered.

Another note on these accounts is that you can set up multiple beneficiaries. For instance, if life insurance isn’t an option for you, then you can have a payable on death account set to pay some amount to a dependent you have with the remainder going to the charity.

There’s also a slightly fancier route that I personally utilize — a donor-advised fund. Donor-advised funds are awesome and you should set one up as soon as possible. It’s like an irrevocable charitable giving checking account that you advise. The way to utilize a donor-advised fund in planned giving is to have all your accounts point to your donor-advised fund as the beneficiary. For example, if you used Fidelity, you’d put Fidelity Charitable Giving (with your personal donor-advised fund account number) as your beneficiary.

Integrating a donor-advised fund in planned giving makes everything easier in a number of ways. First, whenever you’re picking or updating your charitable beneficiary, you just go to your donor-advised and set it there rather than figuring out all your accounts individually. Like other accounts, it’s easy to set up the charitable beneficiary for your donor-advised fund.

The second benefit of setting the donor-advised fund as the beneficiary is that it makes it easier on the nonprofit. It helps the nonprofit maintain their public charity status (an important technical detail that comes into play with larger gifts). Plus using a donor-advised fund simplifies a nonprofit’s operations by giving them a check or ACH transfer rather than having to take the time to accept and sell stock. Donor-advised funds also deal well with other more complicated assets that can come up in planned giving.

Give now through your IRA (if you’re over 70 ½)

Do you have enough income so that you don’t need distributions from your individual retirement account (IRA)? You can make direct distributions from your account to a charity anytime in the same calendar year that you turn 70 ½ and any later year after. And you can give up to $100K per year. These are called qualified charitable distributions.

Be mindful that these distributions must go directly to the charity if you want to avoid it counting as income. You can talk with the bank holding your IRA to make sure this direct transfer happens properly.

(Special note: this is a rare place where the direct distribution can’t go to a donor-advised fund. You can still set a donor-advised fund as your IRA’s death beneficiary though.)

Of course, if you’re 59 ½, then you can still make distributions out of your retirement account without the 10% penalty. But you can’t yet make a direct distribution from the account to a charity. Before 70 ½, you’d have to make the withdrawal, realize the income, and then give with the normal charitable gift tax deduction.

How to give away the house after you’re gone, the somewhat easy way

If you have some real estate like a home or other land that you plan to keep until your death, then you can donate your real estate through a charitable deed. (A deed is a legal document that denotes title of the property.) Here, you’re giving a retained life estate with a charitable remainder. This means you get to use the property during your life and it’s automatically donated upon your death.

Because giving a charitable remainder through a deed is non-revocable, you get a tax deduction. There are some catches though. You’ll want to meet with an attorney to set this up. Fortunately, this isn’t that hard, so it shouldn’t cost you that much. The benefit you get from the tax deduction should more than cover the cost. There are also varying state laws on this, so you’ll want to check to see that this option is fully available to you.

You also want to make sure you’re not creating a burden to the nonprofit you’re giving to. To make sure you aren’t, give the property to a donor-advised fund. Let the bank of the donor-advised fund know and they’ll evaluate the property to see if it’s highly marketable. If it is, they may choose to accept it. Should they accept the property, your donor-advised fund will get the cash value from the eventual sale. That’s a much better deal to the eventual nonprofit recipient. In this case, your nonprofit gets a check instead of having to waste staff time on real estate intricacies.

Of course, if it really is a property that the nonprofit can benefit from, then talk with the nonprofit directly. The same charitable deed procedure still applies.

Be aware that when you give through a deed, you’re only referring to the permanent structures on the property and the real property itself. So this doesn’t include any non-permanent fixtures, furniture, or collectables inside the home. Those are your personal tangible property, which we’ll get to later (spoiler: your favorite nonprofit probably doesn’t want your grandmother’s china dish set).

Also, if you’re less sure about what will happen to the property in terms of sale or ownership, look to the section on wills.

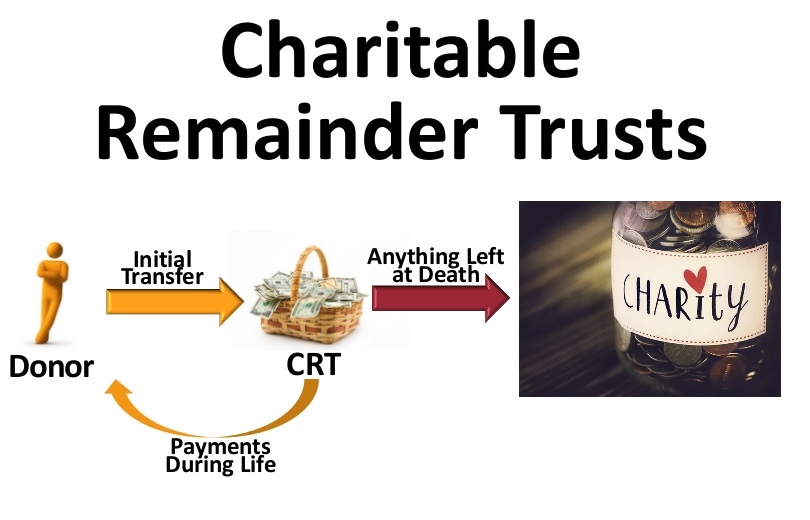

Get paid and give at the same time through irrevocable charitable remainder trusts

A trust is an account that’s generally managed by a bank. It’s its own entity, if you can wrap your head around that. Trusts vary depending on the type. They can start with some set of assets, even complicated assets like real property, closely held stock, or intellectual property rights. They can sometimes even accept more assets depending on the type and have distribution triggers based on time or events. We’re talking about irrevocable trusts because those are the kinds that give you tax benefits (as opposed to revocable trusts).

Trusts are the most complicated tool we’ll talk about. Fortunately, there’s been some development in this space from something called a KISS trust. A KISS trust is more automated with boilerplate language. It’ll get the job done much cheaper for many trusts. The minimum contained within this trust must be $1K, which is actually really low. When you consider cost, you’ll pay much more going to an attorney, which may still be the best option depending on your needs.

When might you need a trust? Imagine you have $1M in stocks and you’re 80 years old. You could put those stocks in what’s called an annuity trust with a charitable remainder. That type of trust will pay you a set amount of money for the remainder of your life. When you die, the remainder will automatically go to the charity you choose (I’d recommend it go to a donor-advised fund for distribution). An annuity trust with a charitable remainder is nice because you don’t worry about outliving your money. Instead, you get an immediate tax benefit, and the charity gets the assets upon your death. This is not a hard one to set up.

Say you’re only 35 and have come into $5M. Here, you can set up a unitrust with a charitable remainder. A unitrust lets you take a percentage of the funds out each year, and you can continue to add to the trust if you like. Again, you have income for life, you get an immediate tax benefit, and the charity benefits upon your death.

In either of these scenarios, if you find that the distribution from the trust is more than you need, then you can either put it back in the trust (if it’s a unitrust) or donate it right away to charity since you have all your needs met. Also, you’ll find that there are certain rules that require the charity to be likely to get at least ten percent of the overall trust amount. Some fancy tables will determine this, which a service or professional will handle for you. Remember that trusts can be funded with complicated assets, so keep that in mind when talking with a professional if that applies to you.

(Technical note: If you’re not quite up in years yet and have extra money, then you could also purchase an instrument called an annuity (different from an annuity trust). That’ll take care of your lifetime expenses. Though a regular annuity isn’t tax deductible, it can start to take care of your lifetime expenses immediately. With your regular lifetime expenses taken care of through the trust payout, that means you can start giving any other financial surplus right away to the charity.)

The more complicated trusts, trusts with real property, and flip trusts

We’re out of the KISS trust range. You’ll really need an attorney and financial planner for these trusts as well as some significant assets. If you’re going to an attorney, then a trust will likely only make financial sense if it has significant funds. That amount could be $50K or much more depending on the complexity of the trust and its assets.

You can put real property like a home to fund a trust that has a charitable remainder (preferably going to a donor-advised fund). You get the same benefits of other charitable remainder trusts as you do when it’s funded with real property. You can even still have access to the property while you’re living (called a life estate interest). Note that there may be some limitations if you’re currently living on the property. In those situations, you’ll want to consult an attorney on your options and consider the charitable deed option discussed earlier.

Another type of trust, called a flip trust, is convenient for complex assets like types of real property with unpredictable marketability or closely-held stock. Closely-held stock is the kind of stock you get when you’re an owner of a private company. This stock isn’t publicly traded. This stock also has the potential to jump in value depending on the company.

By placing the asset in a flip trust, the trust doesn’t trigger until an event you decide occurs. This could be a sale of a company or property. Once the trigger occurs, this has the same benefit as other charitable remainder trusts of providing you with an income, getting a tax deduction, and having the remainder go to charity.

Don’t need the entire amount for lifetime income? Give it all (or what you don’t need) to a donor-advised fund, let them handle the complexities, and indicate which charity you’d like the cash to go to. If you want part of the funds for income, you can do a mix of donating now and setting up a flip trust for the remainder. Talk with your financial advisor or attorney about a solution that partitions the assets in a way the meets your needs.

Wills—when there’s not another way

Should you have a will? Yes, you should have a will. And you should update it every five years or so.

But it is a ton easier for you (and your executor) if you set up your financial accounts to have an automatic beneficiary. Setting up a beneficiary for those financial accounts may also avoid taxes that could hit by giving through a will. Using those tools will also simplify your estate for your loved ones. Those tools (including trusts) also don’t leave you open to creditors the way wills do.

A will should be for what you can’t simplify by other means.

Simple wills aren’t challenging. Publishers like NOLO will help you set one up yourself. There’s easy software to do it, too. If your will is more complicated, there are plenty of attorneys out there willing to help even if it means looking over what you’ve drafted.

That said, I’d recommend against using a will as your primary tool for giving. Use those beneficiary accounts. Trusts (if they make sense for you) are also easier as they too avoid probate.

Again, using a will, it can take over a year for a nonprofit to see any of those assets after you die. All wills go through probate, and it is time consuming. It’s expensive for the estate too if you have complicated and large assets. Accepting assets through wills can also require administrative resources from the nonprofit that takes them away from more important mission-based activities.

So when do wills make sense?

If you have a loved one who needs your home after you die, a will would be a good way to do it (many states also let you handle this through a deed). Perhaps you expect many years ahead of you and don’t plan on staying where you are forever. A will could be an easy solution here when your future is less predictable.

Wills are also good for tangible personal property. Think jewelry, clothing, collectibles, cars, that kind of thing. Those are the kinds of things you can give to family and friends. A nonprofit would have more trouble dealing with and selling these items (unless it’s a Goodwill store or a place that regularly deals with these items). If you wanted the charity to benefit from them (assuming you haven’t realized a large appreciated value), it’s probably just easier to sell the items and give the cash.

If you’re going to name a charity in your will, then I would recommend giving the charity a remainder interest of your estate. A remainder interest is everything left after everyone else is taken care of. Also, make sure that charity is your donor-advised fund if you can. That’ll make sure all the assets the nonprofit gets are highly liquid and they don’t have to do any distracting administrative work. Giving a remainder interest to charity is also a good catch all in case you missed any assets you forgot or didn’t know you had at the time of your death. You can also include a contingent beneficiary (another charity or person) if the donor-advised fund or original charity isn’t able to accept a certain type of asset from your estate.

A final note on giving and wills. Don’t put any restrictive contingencies on the assets you donate. Same for any other giving. There’s a reason many nonprofits throw an overhead fee on restricted gifts. If you believe in the nonprofit you’re giving to, let them decide how to best put your gift to use. Trust them. They think about this a lot. If you really don’t trust them, consider giving to a different nonprofit.

Quickly summarizing all that technical stuff you just read

The basics of planned giving are easy. Every account you have, make sure you have a charitable beneficiary, preferably pointing to a donor-advised fund that has its own charitable beneficiary. Not only is this easier, it’s often actually preferable to other means such as a will because it avoids creditors and sluggish probate court after you die. It also can’t be challenged like a will can. Plus, it can also sidestep paying avoidable taxes. Set this up.

If you have more money than you need and you’re over 70 ½, then you can give through your IRA without realizing income.

If you have real property like a home or farm, then you can give a retained life estate with a charitable remainder. You may be able to set this up in a trust to earn income in the meantime. If you plan on living for awhile longer and expect to potentially sell the property to purchase something else, then including the property in your will may be a good idea. If you give it to charity, then it will likely have to be a highly marketable property.

If you have a bunch of money and you want it to give you income during your life, you can set up a trust and give the remainder to a charity when you die. If you expect to be around a long time still, you might have to add more to the trust. Or you can purchase an annuity for regular income and give more while you’re living since your regular expenses are taken care of.

And if you have assets that require an event to occur such as a sale, then consider a flip trust. Like a trust involving real property, you’ll want an experienced attorney to set this up for you.

Don’t waste time. Set up your current charitable giving plan, get a donor-advised fund, and set your charitable beneficiaries for all your savings and retirement accounts. Then talk with your financial planner and attorney about your more complicated assets. And once you’ve accounted for your financial obligations, give the rest now.

Now that you’ve set up your planned giving

There are lots of benefits to setting up your planned giving. One is that, because it involves thinking about your financial obligations, it can provide you a lot of peace of mind. You’ve planned for those who financially depend on you, including yourself.

It’s good to have long-term finances planned out. That’s particularly true as you get older and have (hopefully) more financial security. Having your finances planned out means that you know what your needs really are. Plus, once your needs are clear, you can give everything beyond that. And you get to enjoy giving while you’re alive.

You should also let the nonprofit know you’ve included them in your planned giving. Many nonprofits have “legacy clubs”. Being in those clubs could open up perks like being a sort of ambassador to encourage others to consider planned giving. Plus, as I alluded, having your finances clarified often means being able to donate more in future years, including the near future.

There’s another reason to let the nonprofit know you’ve included them in your planned giving. Those people who work for that nonprofit. They’re real people, and they like to hear about generous people like you. You’re going to make them grateful and feel awesome. Your gift — likely bigger than you could ever give otherwise — is going to help them do a bunch of awesome work. And that makes anyone’s day.

Finally, you should carefully consider the types of charities you give to. You’re likely to have much less impact donating to a university, hospital, museum, or church. Consider learning about effective altruism to maximize the impact of your giving. The Center for Election Science, which I run, is also really awesome if you want to fix up our failing democracy.

Congratulations on your journey to set up your planned giving. You’re among an admirable minority who take these important steps. There is a lot of avoidable suffering in the world. So give well and make the world better. Also, if you found this helpful, please share this essay with others. The vast majority of people die without any planned giving in place. That needs to change now.

Once you’re all set up, go tell a friend about planned giving. Then, every time you persuade someone to set up their planned giving, you can muse about all the future good you just created.