So You Want To Start A Nonprofit

June 12, 2020

(Originally Published in the Charity Entrepreneurship Handbook)

I’m so glad that your ambition and kind heart have led you to start a nonprofit. Let’s look at what you’re in for.

Step 0. Line Up Those Ducks

The first step to starting a nonprofit is to double check whether you should start a nonprofit. That means making sure you have a strong case for your cause area, a plan that makes sense, and an initial board of directors.

EA factors

Looking at the world through an effective altruism (EA) lens means you’re already considering key factors:

Neglectedness. Are others working on this cause area? If they are, are they addressing it in a very different way?

Importance. If it does what it’s supposed to, will it make a big impact?

Tractability. Will it succeed and catch on?

Does your cause area and the way you’re approaching it let you confidently check off those boxes? If yes, great. If not, best to think some more.

You may also consider if you’re better off as a for-profit. Separately, consider if you’re really handling enough money or taking on enough risk that it makes sense to incorporate.

The plan, the plan!

How’s your plan looking? How exactly are you going to bring about the outcome that you want to see? One gut check is to reflect on whether the logic for the activities you’re doing makes sense. You can do a quick bird’s eye view using a logic model. Here’s the gist taken from a CDC program:

The concept behind a logic model is seeing the flow of logic from the starting resources and activities to the impact you ultimately want to see. Like many models, there are many ways you can formulate them. The main component to keep in mind is that you’re not overlooking key elements and that the flow of logic is sensible.

There is a much more involved planning document called a strategic plan. You would likely benefit from having that document at this early phase — even if it’s more of an initial framework. It’ll make it easier to update and plan, too, by having it early on.

A strategic plan should include areas like:

Organizational description, history, and problem/solution statement

Key performance indicators laid out by years

Environmental analysis including SWOT analysis

Strategy and tactics for how you’re planning to hit key performance indicators

Wins (to fill in later)

Organizational chart

Current resources

A strategic plan is a living document that should be looked over and updated at least annually. They normally span for a three-year period. It may be possible to look further than that if you’re in a highly predictable space or have a predictable long-term budget.

Having visions

Every organized business or nonprofit has a vision and mission statement. This may sound corny, but these are very helpful to reference. This is your base. If you’re considering some activity or project and it doesn’t move you towards your vision and mission, then think again.

First, what are these things? A mission statement looks at your core current and near-future activities and what you’re working to accomplish. Your vision statement says how you would make the world look in the long-term if your vision were completely successful. These should be simple and not overly complicated. Making this will be harder down the road when you have many board members, so best to do a good job from the start.

Here are some examples of good mission statements:

Public Broadcasting System: To create content that educates, informs, and inspires.

Environmental Defense Fund: To preserve the natural systems on which all life depends.

TED: Spreading Ideas.

Smithsonian: The increase and diffusion of knowledge.

Did you notice how they focus on actions and are succinct? That’s not an accident.

And here are some examples of good vision statements:

Oceana: To make our oceans as rich, healthy, and abundant as they once were.

Habitat for Humanity: A world where everyone has a decent place to live.

Feed the Children: Create a world where no child goes to bed hungry.

PAN Foundation: A nation in which everyone can get the healthcare they need.

Notice how these focus on the future and desired end result? Think of this as honing in on a utopia within a problem area.

The easiest mistake to make here is trying to include every single aspect of your nonprofit into your mission and vision statement. If you can’t easily memorize your mission and vision statement, you’ve probably erred somewhere.

Build your A-team

You need to find at least three people (chair, treasurer, and secretary) to join your board of directors. These folks should be just as zealous about your idea as you are. Make sure your chair is someone you can work closely with and get along with during challenging times. You really want that treasurer to have an accounting background if you can. While we’re here, you should also get the online version of Quickbooks after things get moving. (Quickbooks is good for compatibility with other tools down the road.) Finally, your secretary should be reliable and organized.

If you have someone eager who has a strong technical background in your space, but they don’t have the time, then consider creating an advisory board. That can add not only a great informational resource for your organization but also credibility. Credibility can be really important early on.

There are lots of factors for what makes a good board member. It’s enough to warrant a separate article. You should also be prepared to eventually get insurance for your board of directors, called Director and Officer Insurance. Some people will not join your board until you have this as an extra way to shield board directors from liability.

Step 1. Getting Your Organization’s House In Order

You’re going to need some internal rules. You can take all the templates you like from The Center for Election Science transparency page.

Internal rules have a pecking order in terms of what trumps what. Here’s that order:

Governmental law & regulations (out of your control)

Articles of incorporation

Bylaws

Board policy manual

Employee handbook

Your initial focus will be your bylaws and board policy manual. One key tip to keep in mind with all of these documents is to write them simply in a way that is easy to understand. There is no legal requirement that documents be confusingly written or to include archaic language for them to be binding.

Thou shall henceforth and herewithin the aforementioned documents effort and endeavor to convey written verbiage succinctly and without having utilized superfluous, discombobulating, or nebulous language.

Don’t write this nonsense. Write simply. Nobody wants to read that crap. In practice, it will be hard enough to get your board members to read these documents as it is.

(A fun bit of contract law: If part of a document is ambiguous in its language, then it’s interpreted to favor the one who didn’t write the confusing language.)

Let’s set some ground rules

You have to have internal governance documents. Aside from your articles of incorporation (discussed later), your bylaws are the core rules of your organization and are required. These don’t change often. Here are some items your bylaws should include:

Your mission and vision statements

Location (can be broad if you need it flexible as a virtual organization)

Whether you are a membership organization or a directorship organization (you have members that can vote or only those on the board of directors can vote)

Minimum board size and officer positions

Order of policy ruling (this is helpful for others to reference)

Severability clause (keeps the rest of the document valid if one part is invalid)

Procedure for amending the bylaws

Whether the organization runs of a fiscal or calendar year

The board policy manual goes is a bit different. It goes into the details of your organization’s rules, not just the high level stuff. This can be amended more often.

Here’s a table of contents to give you an idea of what this document would include:

Part 1: Policy Manual Purpose

1.1 Description and Origin.

1.2 Purpose.

1.3 Transition.

1.4 Changes.

1.5 Maintenance of Policies.

1.6 Context of Other Policies.

Part 2: Board of Directors

2.1 Purpose.

2.2 Powers.

2.3 Duties.

2.4 Limitations.

Part 3: Board Members Individually

3.1 Powers.

3.2 Duties.

3.3 Terms and Resignations.

3.4 Limitations.

Part 4: Officer Roles & Duties

4.1 Purpose.

4.2 Chair.

4.3 Vice-Chair.

4.4 Secretary.

4.5 Treasurer.

4.6 Parliamentarian.

Part 5: The Executive Director (ED)

5.1 Powers.

5.2 Duties.

5.3 Limitations.

Part 6: Board Meetings

6.1 Types.

6.2 Procedures.

6.3 Voting.

Part 7: Global Policies

7.1 Whistleblower.

7.2 Conflict of Interest.

7.3 Compensation.

7.4 Financial.

7.5 Indemnity.

7.6 Non-Liability.

7.7 Sexual Harassment.

7.8 Non-Discrimination.

Because your governance documents are used so often, make sure that you are careful in their drafting and that you know them well.

The committee for getting things done

Once you’re fortunate enough to have more than three board members, you should consider committees. Committees are a way to make sure things get done without using the entire board’s time.

Committees may be standing (ongoing) or ad hoc. Standing committees are ongoing whereas ad hoc committees are bound by time or an event such as completing a task.

You don’t want to get carried away with making too many standing committees. But here are a few to start with when it’s possible:

Evaluation Committee. The board is responsible for evaluating the executive director, programs, and the board itself. This committee coordinates that process.

Governance Committee. When you’re considering language before the board to change some part of a governance document, the governance committee does the initial legwork and makes recommendations.

Board Recruitment, Training, and Onboarding. A committee helps make sure there’s a clear process and experience for new board members and a way to add more fresh faces.

Whenever you form a committee, the board needs to create a committee charter first. Without this, the committee will be flying blind, doing either nothing at all or worse — things they shouldn’t.

A committee charter should have these components:

Name. Keep it descriptive.

When formed. When the board formed the committee.

Permanence. State whether the committee is standing or ad hoc; and if it is ad hoc, it should state what determines its completion.

Powers. Can it act on behalf of the organization and if so, what capacity? Can it add its own members without the board?

Members. Who is on the committee and who chairs the committee?

Purpose. Simply — and I do mean simply — what does the committee do in broad terms and why does it exist?

Tasks. What specific tasks does the committee do?

Typically, the executive director and chair are automatically members of all committees. While normally the executive director does not take a voting role for the board (and is typically not considered to be on the board), there is an exception with committees. In committees, the executive director typically may vote. Of course, like any vote, the executive director may not vote when there is a conflict of interest.

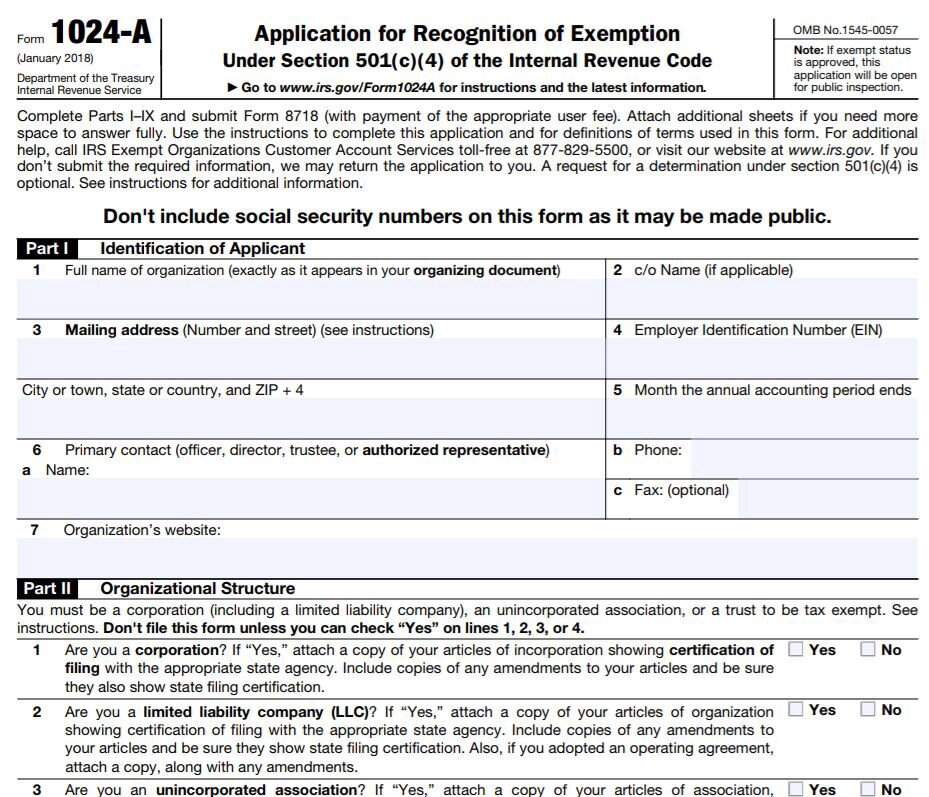

Step 2. The Bureaucrats Want Their Papers

Your eyes may glaze over on this section. It’s not very exciting, I know. But at least be glad that you’re not figuring out paperwork for a 501(c)4. The IRS does not care about your pain.

There’s variability depending where you incorporate, so this may not be an exhaustive list. Here’s a nice reference where you can learn more about your particular state. Note that some of these forms need to be renewed every one or two years. It all varies. You’ll likely need to make a spreadsheet for your individual state. I’m sorry.

Home is where you incorporate.

You generally want to incorporate where you have the base of your activities, particularly where you’ll be doing a lot of fundraising. You can find your articles of incorporation template on your state’s secretary of state website. If they don’t have a specific one, you can search other corporations using the corporate lookup tool which these sites normally have. Once you find some other nonprofits, you’ll have a template you can work from. You can also use your secretary of state’s website to check to see if your nonprofit’s name is available. While your primary place of business may be in one place, you are technically allowed to incorporate in any state. So consider your options as states have different levels of bureaucracy.

There are some sections that are generally required. One is the dissolution clause. This just says what the organization will do with the assets it has if it has to close up shop. Generally, the answer is to give it to another nonprofit that aligns with your organization’s mission, after paying any debts.

Here’s an example:

The property of this corporation is irrevocably dedicated to charitable purposes and no part of this corporation’s assets will ever benefit any director, officer, or member of this corporation or any private person. Upon winding up of the corporation, its assets after handling all liabilities will be distributed to a nonprofit fund, foundation, or corporation which is organized exclusively for charitable purposes and has its tax exempt status under lnternal Revenue Code section 501(c)3.

Other clauses are also common such as expressing limitations.

“This corporation is organized and operated exclusively for charitable purposes within the meaning of lnternal Revenue Code section 501(c)3.”

“The purpose of this corporation is subject to the limitations of these articles as well as state and federal law.”

Your individual circumstance may vary, but generally, the most flexible type of nonprofit is a public benefit nonprofit. You often have to state this in your articles. To learn what suits you specifically, however, I’d recommend checking out this 50-state resource.

You just got served!

Or, if you did get served— sued or prosecuted that is — who would the person be who got the papers? This person is called a resident agent (may also be called a registered or statutory agent). I use that term “person” loosely (really loosely) because a corporation can also be a resident agent. All a resident agent does is accept notice papers if you’re sued. That’s all. But you have to designate someone.

Who would be good for this? My personal preference is to not use a person because people move around and come and go. Corporations, however, can be more reliable. You can technically change who your resident agent is whenever you want, but it’s convenient not to change these things when you don’t have to. There are lots of places that offer these services for many different states. Here’s one of them. You register your resident agent for your nonprofit through your state’s Secretary of State website.

You’ll also need a corporate address. If you’re virtual and don’t have a physical address, I’d recommend using a corporate address with the same service as above. There can be delays and complications when you change your address many times, which is why I recommend this for virtual organizations. You should provide this address to others only in cases when you need a technical physical address.

Fundraising? That’ll be another form.

Most states require that you file a form for charitable fundraising. Here’s a good reference from NOLO on which states do. You’ll also have to figure out which state agency to register with. It’s different in many states.

Do you really need to register in your state? If your state rules say yes, then yes.

What about registering out of state when you’re doing fundraising in other states? The answer is more challenging there. The IRS has recently attempted to guilt trip nonprofits by asking them lots of questions about requirements they’d like to see but aren’t in place. One of these is where they’re registered to solicit charitable donations.

In practice, if you have a focused fundraising campaign in a state and you’re bringing in funds there, then you should probably register if they require it. If you passively get some online donations from a state and that state’s rules are so absurdly broad that they require you to register, then it’s unlikely anyone is going to chase you down.

About a dozen states have absurdly low triggers for registration without exceptions for nonprofit size. In practice, only the largest nonprofits register in every state to address this. It is very expensive and complex to fulfill registration requirements for every state every year wherever you get a donation.

If you’re fundraising out of state and you’re not registered in that state and you get reported, then you may either get a warning or a fine until you register. This will vary from state to state. There is technically a form that is intended to make it easier to register for multiple states at once. Unfortunately, because all the states agreeing to use the form added a bunch more requirements it made the whole point of a uniform form pointless. Go figure.

These fundraising registration forms must typically be filed annually. Like many forms, they come with regular fees, too.

Officers on your board? I’m gonna have to ask you to register those.

Again, there will likely be a form on your secretary of state’s website for you to state your officers. This is typically one of those forms you have to renew in the future. Most states ask for this.

What’s your number? Your Employer Identification Number (EIN)

All corporations need this. Fortunately, you can do it online and it only takes 15 minutes. Just go through the prompts on the IRS website.

After you get your EIN, write that number down because you’re going to use it on a bunch more forms.

Form 1023: the form you’ve been waiting for

The Form 1023 is the IRS form that you file to get the IRS to recognize your 501(c)3 status. This is going to be your first big win. Unfortunately, the IRS can be highly variable in how long it takes for them to do their end of this process, particularly if you do anything that appears remotely political. Fortunately, you can expedite this process with some extra steps.

Also, here’s a whole website designed to make Form 1023 easier. To download some of their samples, they only ask for a trivial donation. Totally worth it.

When you finally do get your recognition letter, scan it. You’ll need it a lot in the future. I also recommend making this easy to find on your eventual website on something like a transparency page.

Step 3. The Long and Winding Road Ahead

Naturally, this is only the beginning. Here are some general strategies and resources to leave you with:

Be particular about hiring. Here’s an article on just that.

Make a good budget. Budgets are important and finding a good template in the beginning can be a pain. You can find a budget template and other templates on this “Goodies” page.

Take good care of your employees. Make sure you have a culture of open feedback (more challenging than you might imagine). Prioritize giving them good pay and benefits. Thank them genuinely as much as you can. You probably can’t do it enough.

Automate what you can. Repetitive tasks take up time. With few people, you have little time and tons of important things to do.

Outsource what you can. You only have time to learn so much. Outsourcing is great for technical tasks that will take you too long to get good at. This is especially true for things like payroll which can be done through places like Gusto or Zenpayroll. You should also find a good nonprofit accountant. That person will also be helpful when you eventually have to file your first annual nonprofit tax filing (Form 990).

Take advantage of nonprofit benefits. These include benefits like Google Suites for nonprofits, which includes as many email addresses as you need and Google Grants ($10K/month in AdWords). Techsoup also lists lots of discounts for nonprofits. (Always look for nonprofit discounts.)

Use minimal viable product strategies. Much of what you do will not be perfect the first time around. Work first on getting usable functions and demonstrate proof of concept before scaling. Consider this for your initial activities and ongoing projects like your website with the understanding that they can be built upon later.

Celebrate successes and share them. You need to share your wins and progress. You’ll also want to fancy that up in an annual report. This is what lets others know whether you’re succeeding. Your email list will also be one of your most cherished possessions as that is how you keep your base updated. (In the beginning, something like MailChimp will be fine.)

Track your donors. A nice way to start up your initial donor database is through donor management systems. There are many. A nice starter one is Little Green Light. It will have limitations. Eventually, you may outgrow this one, but it’s good to start on.

Find online learning resources. You can find great resources from places like BoardSource, Bridgespan, and National Council of Nonprofits.

Find some good books. Spending multiple weekends in your library’s nonprofit section is a totally reasonable plan. Also, NOLO has lots of nonprofit resources, including lots of nonprofit books. For sure, without any doubt, pick up their intro on nonprofit incorporation. Just buy that now. For advanced topics, pick up anything by Bruce Hopkins at your library, particularly The Law of Tax-Exempt Organizations if you can get your hands on it. His books are very expensive but detailed.

Crowdsource from nonprofit communities. There are some great Facebook groups for nonprofit professionals like ED Happy Hour and Nonprofit Happy Hour.

Check out the essays I’ve written. I write a lot about the technical aspects of nonprofits and philanthropy. You can find my essays cataloged on my personal website. I try to be a firehose for useful information.

After you’re done with all these forms and checklists that will continue indefinitely, don’t forget to do those things that involve improving the world. You can do it, and good luck!